The Curtiss-Wright Model 2500 Air Car

Believe it or not, the Curtiss-Wright Model 2500 Air Car almost became a commercial success. And it did that without having to look like a Blade Runner prop.

In 1959, the U.S. Army’s Transportation Research Command was looking to induct a small-to-medium capacity all-terrain troop transport. Mind you, this was a time when everyone, and by everyone we mean GM, Ford, Goodyear, Renault, Fiat, Yakovlev, McDonnel, and many other non-aviation companies were gunning for helicopter contracts.

Curtiss-Wright, but, was one of the largest plane builders in the U.S. They had built legendary warbirds like the P-40 and the SB2C Helldiver. Needless to say, the U.S. Army sat up and took notice whenever a new Curtiss-Wright took to the air.

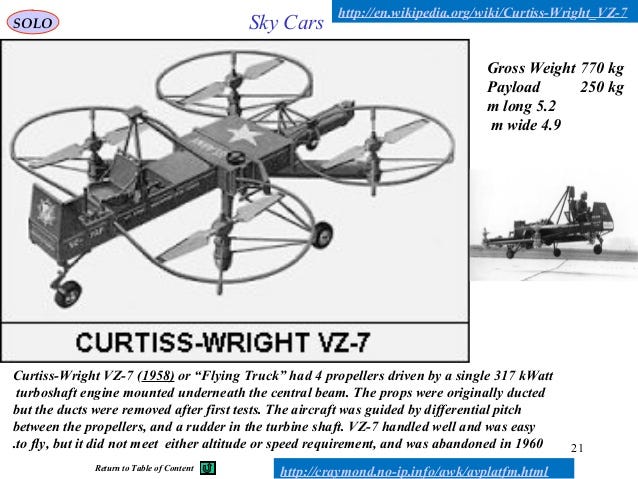

When they heard that the veteran plane builder had a few short-takeoff-landing (STOL) designs in the works, they asked to come over. Surprised Curtiss-Wright management agreed, and thus, the first concept, the VZ-7 was shown to them. It was to be a flying Jeep — a go-anywhere weapons platform that could seat four best suited for reconnaissance.

But, there were problems — and very serious ones.

The four rotors ran off a French turboshaft engine that developed 425 horsepower. And they were quite exposed, which made the VZ-7 very easy to shoot down. It had a blistering top speed of 32 mph, and a service height of 200 ft. The pilots were completely unprotected, and flying it in severe weather was impossible. The engine was so loud that you could hear it from miles away. The U.S. Army received so many complaints from test pilots, engineers, and people living near test bases that the VZ-7 was sent back to the factory.

It was an embarrassment, sure, but the Curtiss-Wright Corporation learned from their mistakes and went back to the design shop. This time, instead of using rotors for full-fledged flight, they utilized something called the ‘ground effect’. According to this concept, the closer a rotor is to the ground, the lower the drag, and the higher the lift. The best example is a hovercraft. It has a fan run off the engine that creates a cushion of air. The air, operating under the ground effect theory, supports the entire weight of the hovercraft.

Curtiss-Wright built the Model 2500 Air Car using this idea — in 1959.

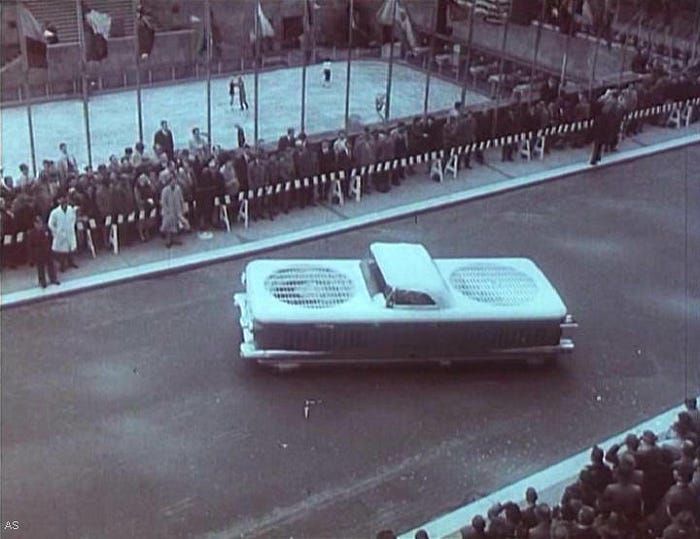

The Model 2500 Air Car was ahead of its time because it was more road car than a plane. It had seating for two or four, blinkers, a windshield, and — looked like a real car. You could get in and out of the car without having to worry about the rotors. The vehicle rode 10–15 inches off the ground so you couldn’t shoot it down.

The Curtiss-Wright Air Car was powered by two Lycoming engines rated at 180 horsepower that ran fans located in the fore and aft of the car. The engines ran two low-speed fans that created an air cushion. The mechanicals lived inside a large car-like body borrowed from Studebaker-Packard. It might have come from Curtiss-Wright’s tie-up with Studebaker-Packard in 1956).

The Model 2500 had a steering wheel for directional control and a boat-like throttle. To speed up, one had to pull it up, and pushing it down slowed the vehicle. The steering and braking worked by controlling the speed and direction of the fans powered by the engines. Turning the wheel in one direction operated a set of louvers that pushed air out the opposite way. To speed up, the engine throttled up, and the fans were set at a forward angle (or positive angle of attack).

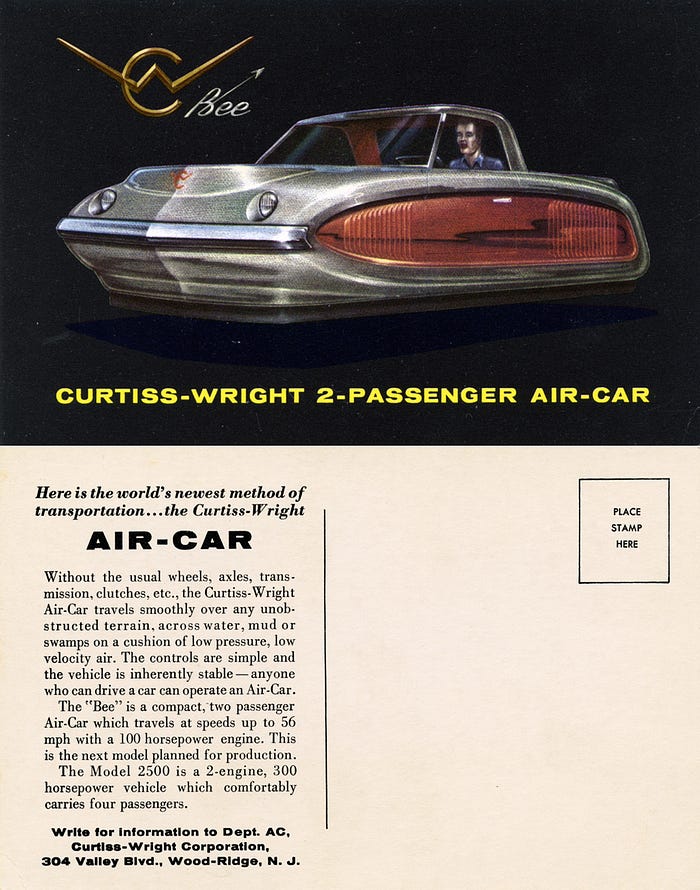

The Model 2500 came in a variety of configurations. There was the base model, which had the Lycoming engines, and could seat two. It was called the Hippo and the U.S. Army’s Transport Research Command ordered two examples. There was a commercial model, which had a wider bed and could be considered an air-truck. There was a coupe-style design, too, called the ‘Bee’.

By the 1960s, the U.S. Army tested the hell out of the two production examples and deemed them unsatisfactory for Army use. We can imagine why — The inherent problems of ground-effect mobility came back to haunt them. You see, while the air-cushion idea worked well on smooth ground, and on water, it faced severe problems on inclines. The Curtiss-Wright Air Car couldn’t tackle anything beyond a 6% grade (a slope that rises 6 feet every 100 feet). Then, there was the noise. Imagine sitting a couple of feet away from an unmuffled helicopter engine. Any extra sound insulation meant more weight, which would slow down the Air Car even more. Helicopters were faster and had the range to get troops from the base to the front line. The Model 2500, if inducted, would serve as VIP transport, for which the Army already had the tough-as-nails Jeep. So, the Model 2500 Air Car, too was rejected for military use.

21 feet long, seven feet tall, and eight feet wide, the Model 2500 Air Car wasn’t exactly small by passenger car standards of today. But it was the 1960s — the era of excesses when anything was possible, so it fit right in. It weighed 2,770 lbs, which was comparable to most medium-sized cars of the day. Somewhere down the developmental journey of the Curtiss-Wright Model 2500 Air Car, the management fell in love with the idea — because they wanted to sell it to people like you and me. You could buy one for $15,000, which translates to $133,557 in 2020 money. That’s at least half of what a real flying car costs today.

Out of the two surviving examples, the only one you should check out is at the US Army Transportation Museum at Fort Eustis, Virginia. The other one’s falling apart.

But hey, now we learn that the U.S. Air Force is looking for ORBs or Orbital Resupply Buses. That’s military-speak for flying buses. Thanks to the USAF’s Project Agility Prime, chances are that the flying car may soar again.

Sources